Drones are all over the skies and the news today. With a military history going back more than a century, more recent advances in technology and miniaturization have allowed civilian aircraft drones to evolve from recreation and filmmaking to be a versatile tool in many industries, ranging from mining to search and rescue. This article explores how urban designers and planners can get in on the action and use drones for good.

A quick word about terminology. Some pilots and enthusiasts actually avoid the word “drone” because of its robotic military connotations. Drones can also refer to a huge variety of different applications and vehicles, including everything from submersibles to package delivery bots. More importantly, it can give the false impression of a machine that operates outside of human control. So, for this article I will stick to the official terms used by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA): unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) or small unmanned aerial vehicle (small UAV or sUAV).

The benefits and uses of UAVs for urban design are numerous and can include:

- Overhead and oblique views for site analysis and supporting conceptual graphics/overlays.

- Detailed yet wide contextual views of buildings, sites, streets, and neighborhoods.

- Work at multiple scales, from a single building, block, neighborhood, or skyline.

- Marketing materials and general project support images.

- Inspiring photos and videos for public engagement purposes.

- Before-and-after images to demonstrate the scale of progress for infrastructure or construction.

MAKERS recently employed aerial photography during a visit to Boise, ID to evaluate the design of new developments after we helped the City adopt urban design standards, including a map of block frontage requirements, in 2014.

MAKERS most often uses aerial photography to highlight the existing conditions or context of a particular site, set the stage for discussions about neighborhood planning and design standards, and illustrate presentations and reports with the character of a study area. It has proven to be a valuable tool for engaging clients, community members, and decision-makers who are new to urban design discussions.

Aerial views, especially at oblique angles, deliver value in showing the overall relationships between buildings, streets, and open spaces. UAVs also provide a more real-time look at existing conditions than remote or satellite imagery, which is often outdated by a year or two and not reliably available in small towns and rural locations. UAVs can also create high-resolution top-down maps through simple tools such as Adobe Photoshop’s photo merge function. For more advanced applications, Lidar and photogrammetry can be used to build accurate point clouds for 3D modeling of complex built and natural environments.

MAKERS used aerial photography for public engagement and report illustrations in in a waterfront study for Edmonds, WA.

I’ll dive into the many practical considerations of UAV operations and how you can start using this technology for your urban design needs.

What about regular flight?

Designers who have worked with cartographers or surveyors may be familiar with the principles of aerial photography using regular airplanes or helicopters and wonder how that compares to results with UAVS. Regular aerial photography is best suited for very large-scale needs, such as recording an entire city or rural landscape at the scale of hundreds or thousands of acres. This often involves a special camera built into the body of the aircraft. It’s generally excessive and costly to hire this service for getting general views of a single site or neighborhood, and it takes considerable time to arrange.

Manned flight can be cost effective if you have a DSLR camera and pilot friend you can hire for the cost of fuel and lunch, but a great result is not always guaranteed. A minimum 500-foot altitude, windy and bouncy conditions, and crowded air traffic can make it difficult to capture close-in photos and usable video. Nonetheless, MAKERS has used this method successfully for several urban and rural projects across western Washington.

These examples are views from a Cessna airplane. The scale of the sites meant the context viewable in photos from a UAV may have been limited. Left: The National Guard’s Seattle Readiness Center in the Interbay neighborhood. Right: A strawberry field considered for annexation in Carnation.

UAVs, on the other hand, offer a much more fine-grained, nimble, and cost-effective approach.

General approach

With the principle of “everything in moderation” as a guide, note that relying on aerial images too much for a project could be detrimental – everything looks perfect from far away, and the common gray/brown/green colors of the built environment can start to blur together when seen repeatedly from above. A key role of designers is to understand and convey the everyday human experience in our communities. It’s best to complement aerial images with ground-level photographs, drawings, and renderings. Further, UAVs do not replace the well-established tools that urban planners and designers use for site-specific work. Maps, GIS data, field visits, sketching, tours, 3D modeling, and Google Earth continue to be vital and useful options in the site planning and urban design toolbox.

Speaking of Google Earth, this free software complements UAVs very well in planning shots, finding historical imagery, measuring distance and topography, and more. During flight planning, I make a point to first fly around virtually with my colleagues and clients who are requesting the aerial mission. As the pilot, it helps me refine and comprehend the requested views and angles and for me to explain hazards and restrictions that need to be considered for a safe flight such as powerlines, distances from the launch site, and altitude limits. MAKERS’ partner Bob Bengford has written about the many other benefits of Google Earth for planners.

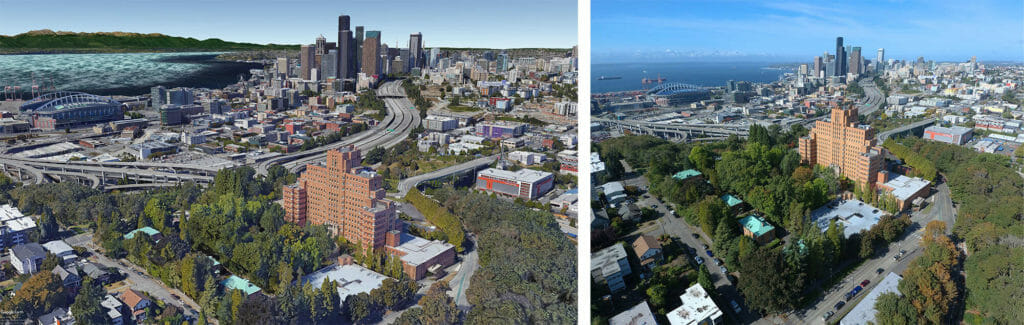

Left: A preflight in Google Earth showing the desired view angle. Right: The actual photograph.

Projects with UAV operations must incorporate the extra time and expense for planning flights and physically traveling to the location. This can be worthwhile when done strategically, such as combining a flight with a trip that needs to be done anyway for a client meeting or public event, or stringing together flights across several locations in a single day for multiple projects. UAV operations are also weather-dependent, though avoiding rain and high winds is already a common objective of designers’ typical field work.

Training

Training is not strictly required by FAA for commercial certification, but it is a good idea for new remote pilots to take a one- or two-day course to learn how UAVs physically operate, understand the complexities and rules of the national airspace system, and get familiar with aviation weather. Perhaps more importantly, find a class that offers practical tips and shares best practices, since this is still a relatively new technology with constantly evolving capabilities and legal gray areas.

Most airports have a fixed-base operator (FBO) that runs flight training services, and many now offer UAV classes. Expect to pay a few hundred dollars. There are also a multitude of free and paid online options, but an in-person class also provides the opportunity to meet fellow aspiring pilots and hear about their experiences and learn from their practical questions. In my own class, I met an Australian cinematographer looking to get certified to work on a film set in the U.S., a real estate agent looking to improve their company’s photography capabilities, and a community activist working to improve street design. A good class will also offer the chance to get your hands on an actual UAV for some practice flights in a safe environment.

Whether you take a class or not, the FAA, aviation websites, LinkedIn, and other sources offer excellent study materials. Research, education, and training will help improve the chances of a smooth certification process.

Commercial certification

A Remote Pilot Certificate is required to operate UAV commercially; that is, if you are flying for your employer or to make money, you are required to be certified and have working knowledge of the FAA’s Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems rule, under Part 107, Title 14 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. Certification is not required for purely recreational or hobby purposes. However, recreational flyers can also benefit from flying under Part 107 because it unlocks the opportunity to fly closer to airports, which can be helpful in airport-dense regions like the central Puget Sound area and Spokane.

To get certified, pilots must take a knowledge test at an FAA-approved Knowledge Testing Center (also usually located at an FBO). The test costs $160. It has 60 questions that will challenge your familiarity with federal regulations, airspace and flight restrictions, weather, aircraft loading and performance, emergency response, radio communications, crew health and safety issues, and maintenance procedures. There are also recurring knowledge requirements, similar to AICP credential maintenance.

Once you pass the test, it’s time to acquire equipment.

Equipment costs

The upfront cost of adding UAV capabilities to your work can be challenging for sole practitioners and smaller organizations. Costs of training and certification are mentioned above, while the cost of acquiring equipment ranges widely. For a minimum level of professional performance, expect to pay at least $1,000 for a UAV aircraft and accessories such as extra batteries. Models at this price point are where commercial users will find essential features, such as:

- A high-quality camera with at least 1080p resolution (2K); 4K resolution is now becoming standard with the trade-off that it has very large file sizes.

- Camera gimbals that keep the image steady regardless of how fast the aircraft is moving or the wind is blowing.

- Maximum flight time per battery of at least 20-30 minutes.

- Controllers that provide real-time information on the aircraft altitude, distance, battery level, etc.

- Pre-programmed flight options, such as grid surveys, orbiting, following, etc.

At MAKERS, I currently fly the Evo model made by Autel, which is one of the few American-based companies producing UAVs for photography. I chose it for another important criteria to consider: portability. The Evo and others in its class fold down to fit in a small camera bag that can be slung over my shoulder or packed into a suitcase. Autel is also one of the few brands which offers a video screen built into the handheld controller, which I find much more convenient than attaching a smartphone for camera controls. Other popular brands with a range of models include DJI, Parrot, Yuneec, and Skydio.

The Autel Evo model we fly at MAKERS.

Aspiring pilots who are not sure they want to take the leap into the UAV world can find lower-cost options to test out first. Simple models in the $200 to $400 range are great for building up your basic flying skills and confidence. Avoid the cheapest options that might be considered toys, as they tend to have very poor flight performance and are impractical for useful photography.

Cost varies greatly when moving beyond basic photography and videos. More advanced UAVs can be found with remote sensing capabilities such as terrain and vegetation scanning (LIDAR), geographic surveying, thermal imaging, and biological sensors. For planners and designers, these features could help with tasks like building a 3D model of a neighborhood in a flood zone, assessing the health of a tree canopy, or evaluating the building energy efficiency of a college campus.

To process remote sensor data or build terrain models, you can purchase additional software or outsource the work to specialty firms.

In the video above, I show the Autel Evo’s capabilities in a variety of environments.

Insurance

Another cost factor is insurance. Insurance is a must, because accidents or malfunctions can cause considerable property damage and injuries, or the aircraft could be lost. More than one headline and YouTube video has shown the results of pilots crashing into buildings, trees, and lakes. Sometimes crashes are clearly avoidable, and other times the aircraft can fly away with a mind of its own and is never seen again. Insurance is important to protect yourself, the business, the equipment, and to hedge against the fact that UAV technology is still maturing.

For large organizations, it should be a straightforward process using a current insurance provider. Alternatively, there are several specialty policies offered by various providers such as DroneInsurance.com or Skywatch.ai, which offer coverage by the year, month, or even day.

For smaller organizations or those that want to ease into UAV ownership, such as the team here at MAKERS, we took a different approach. I retain personal ownership of the aircraft and have insured it under a personal articles policy at home, since I also use it recreationally. MAKERS covers liability insurance for business purposes, through an additional endorsement on the firm’s professional liability policy.

Regulations

Prior to 2016, when Part 107 was adopted, the UAV environment was the wild west. Today, the regulations provide helpful guardrails and safety benefits that all pilots should abide by.

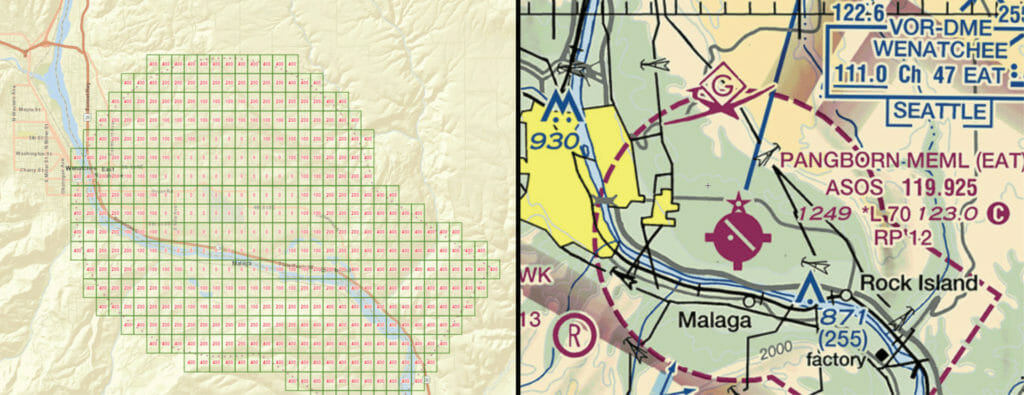

First and foremost, operations are freely in permitted in Class G airspace, which covers most of the country. UAV operations are prohibited within Class B, C, D, and E airspace without authorization. These airspace classifications are typically found within 5 miles of a controlled airport but can vary in shape and distance. UAV operations are also prohibited over military installations without permission. The FAA UAS data map is the best source for quickly locating airspace classifications and flight restrictions. Airspace is important for urban planners and designers, because the communities we work in are often located near civilian and military airports.

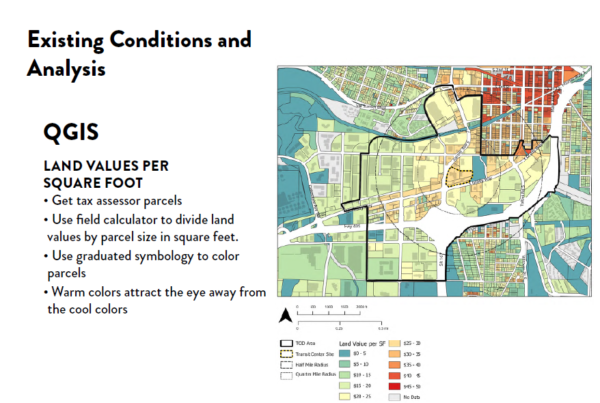

The FAA UAS data map shows altitude limits of 0-400 feet within the Class E airspace around Wenatchee’s Pangborn Memorial Airport. Lower altitude limits are typically aligned to protect the runway approach and departure corridors.

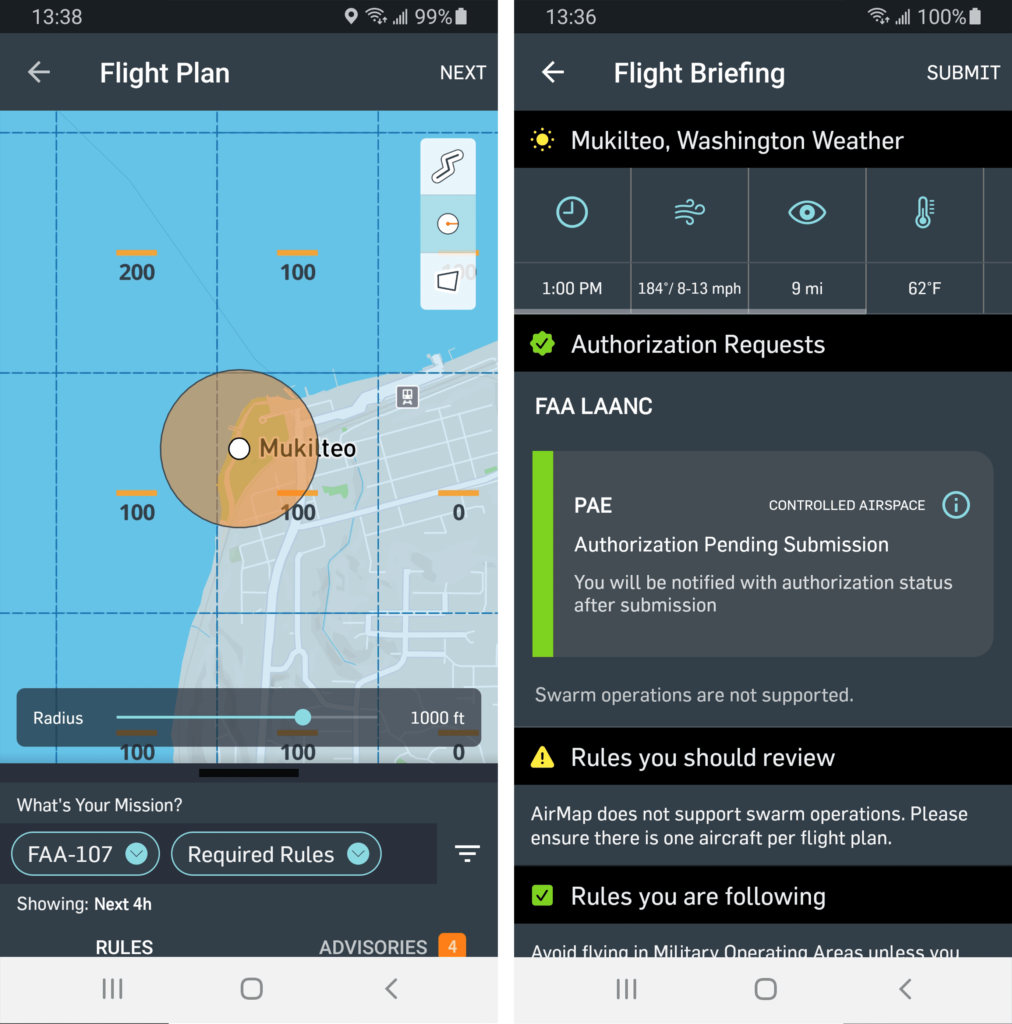

Part 107 pilots can get authorization to fly in Class B, C, D, and E airspace, usually at lower altitudes than normally allowed, through the Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability (LAANC). LAANC permissions are requested through a computer or smartphone app, where the pilot enters information about the future flight area, time, contact information, and other details. Once submitted, the flight will be automatically authorized or denied nearly instantly, and the operation can begin or be revised accordingly. The system is efficient and a major improvement; before the rollout of LAANC in 2018, the FAA advised pilots to submit their requests 90 days in advance.

Samples of the interface in AirMap, one of many LAANC-compatible software applications.

Note that the FAA map doesn’t show some types of restrictions. For example, UAVs are prohibited entirely in national parks and other federally protected sites. In Washington, UAVs are prohibited in state parks without permission, and many local jurisdictions forbid launching in city parks. It is always best practice to investigate the local rules and regulations when flight planning. Search the local municipal code for key terms like drone, aircraft, model aircraft, unmanned, and remote control.

Few if any localities prohibit launching from streets and sidewalks, which I frequently find to be a viable option. Remember to check for overhead utility lines and avoid interfering with pedestrian and vehicle traffic.

The FAA maintains a separate map and list of temporary flight restrictions (TFR) that must also be reviewed immediately prior to every flight. TFR’s are associated with sensitive activities like major sporting or music events, military training, natural disaster response, and presidential visits. The penalties for violating a TFR are substantial.

A view just outside Virgin Islands National Park on the island of St. John.

The other basic regulations are listed below. Some of these can be waived if an applicant demonstrates use of alternative safety methods.

- Maximum altitude: 400 feet (may be lower near airports).

- Minimum cloud separation: 500 feet vertical and 2,000 feet horizontal.

- Minimum visibility: 3 statute miles.

- Maximum groundspeed: 100 miles per hour.

- Operations time: Daytime between official sunrise and official sunset. May operate during civil twilight (30 minutes before/after) if anti-collision lighting visible for 3 statute miles is installed.

- Aircraft must be kept in unaided visual line of sight by the remote pilot in command or visual observers who are in good communication.

- Must not operate aircraft above people and moving vehicles.

- Must not operate aircraft from a vehicle or boat in a populated area.

The above video shows one of MAKERS’ early UAV projects in Snohomish’s Midtown district, giving the community a general overview of infill development opportunities. The video was used on a storyboard and at public meetings. The operation was challenged by the one-mile length of the district, which required multiple flights to meet line-of-sight requirements. Weather was also a factor, with morning fog disrupting minimum visibility and clearances until it lifted.

Beginning in September 2023, all recreational and commercial UAV pilots must comply with a new remote identification requirement. This rule requires UAVs to have a built-in or attached module that broadcasts an identifier, location, and altitude. Only officials at the FAA and law enforcement agencies will be able to connect the aircraft identifier to owner information.

Privacy and property rights

It is obvious that using UAVs for the scale of urban design work means we are not concerned with capturing images of individuals or license plates. However, an observer on the ground has no way to discern the purpose of a UAV hovering over their neighborhood, and it is understandable that many people have general privacy concerns with the technology. Some aircraft motors also can be loud and obnoxious.

The best practice is to avoid flying close enough to people that they could be identified in a photograph or video. If you are following the Part 107 rules and already staying away from people, this is easy to achieve. My rule of thumb is to stay at least 100 feet above rooftops. Be aware there may be people you cannot see from the ground or on your camera feed who are working on a roof, lounging on a balcony, or playing in a backyard. Spatial awareness also applies to public spaces and streets. Never fly over moving traffic, especially high-speed roadways.

The FAA has overriding jurisdiction over the entire national airspace, and there is no set altitude to which property rights extend. That said, common sense rules the day. Avoid undue encroachment or being a nuisance to people living or working on private property. If possible, provide ample notice to property owners or the general public about when, where, and why a UAV operation is taking place. If you are approached by someone while flying, it’s best to immediately pause or suspend the operation, be friendly, and be open to questions about what you’re doing. The most common question I get from passersby is about the model of UAV I’m flying.

In this view of Redmond’s new Downtown Park, no individuals are identifiable. The aircraft is also positioned to avoid impacts to people enjoying the park.

Conclusion

Whether used for site analysis, conceptual graphics, or illustrating a report, aerial photography is an effective way to support urban design with fresh perspectives. When used safely and strategically, the possibilities are virtually limitless. We must also remember that UAVs are tools that do not replace other methods, but it can enhance our work in a rapidly changing world.

Now that you have a handle on the basics, get trained and get flying! We’ll see you in the friendly skies.

Further reading

- APA Quicknotes #79, “Unmanned Aircraft Systems and Planning”

- APA Planning Advisory Service #597, “Using Drones in Planning Practice”

- APA webinar, “Sky’s the Limit: Legal Implications for Drones”

- American Bar Association, Drone Law Committee

- American Bar Association, “Federal Laws, Regulations and Programs Affecting Local Land Use Decision Making [on] Drones”

- Kellington Law Group, “A Planner’s Introduction to the Law of Unmanned Systems”

- Ric Stephens, “Drones and Cultural Lag”

- How to price your drone services, 3D Insider