2023 was a banner year for housing policy in Washington, yielding a bumper crop of state-level bills that address a variety of land use, environment, and financial issues that intersect with housing. Perhaps no legislation has received as much attention or will have as much immediate impact as House Bill 1110 (HB 1110), known as the “middle housing” preemption bill. The landmark bill was sponsored by 28 legislators in a showing of bipartisan support from districts across the state.

HB 1110 opens with this first finding of fact that explains the Legislature’s motivations:

“The legislature finds that Washington is facing an unprecedented housing crisis for its current population and a lack of housing choices, and is not likely to meet the affordability goals for future populations. In order to meet the goal of 1,000,000 new homes by 2044, and enhanced quality of life and environmental protection, innovative housing policies will need to be adopted.”

Indeed, Washington is struggling with interrelated crises in affordable housing and homelessness. Restrictive zoning is one of many reasons why Washington is not building enough homes and why rents are rising, and increasing housing production (whether subsidized or not) is the primary solution for constraining rent growth and reducing homelessness. Costs of housing also affect the use of transportation systems and the urgency of mitigating climate change.

The most common types of housing built in Washington over the past several decades

Across the nation, state-level zoning intervention has gained momentum as state leaders find that local governments are not adequately addressing the issue. California and Oregon, in particular, have recently led the way with requiring that most cities end single-family zoning. That type of zoning is common across the country and typically requires that detached single-family homes be the predominant type of buildings on more than three-quarters of urban land (in Seattle, 81% of the city is single-family zoning). Leaders in Vermont and Montana made similar and popular strides this year, often pointing to California housing prices as a problem to avoid, while the legislatures in Colorado and New York are still looking for traction.

HB 1110 focuses on “middle housing” which is the scale of housing between large single-family homes, (the most expensive type of housing) and large multifamily buildings (offering relatively lower costs but which are often opposed by vocal community members). Middle housing is specifically defined in the bill as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, fiveplexes, sixplexes, townhouses, stacked flats, courtyard apartments, and cottage housing. Middle housing strikes a political and family-friendly balance in terms of price point and greater ability to incorporate features that mimic single-family neighborhoods, such as ground-level units, yards, porches, individual driveways, and low-rise architecture.

Examples of some middle housing types defined in HB 1110. Top center and top right images courtesy of Sightline, other images by MAKERS.

Upzoning and zoning reform can promote housing abundance in communities of all sizes experiencing growth pressures, just as downzoning throughout 20th century America was also effective in promoting exclusion and segregation. In June 2022, Spokane proactively passed an emergency ordinance to allow fourplexes on all residential lots, and the result is over 400 duplex, townhome, triplex, and fourplex units in the pipeline. They are likely to offer price points which are more affordable to more people, as has borne out in Portland after that city’s infill code reforms (also, 99% of new middle housing there is providing family-sized units with 2+ bedrooms). In Seattle accessory dwelling unit permits more than tripled after common regulatory barriers were removed, and in Anacortes housing production diversified after a major code update. These communities are not necessarily reinventing the wheel, but rather returning to the more flexible zoning that existed a century ago.

Minimum Allowed Dwelling Units

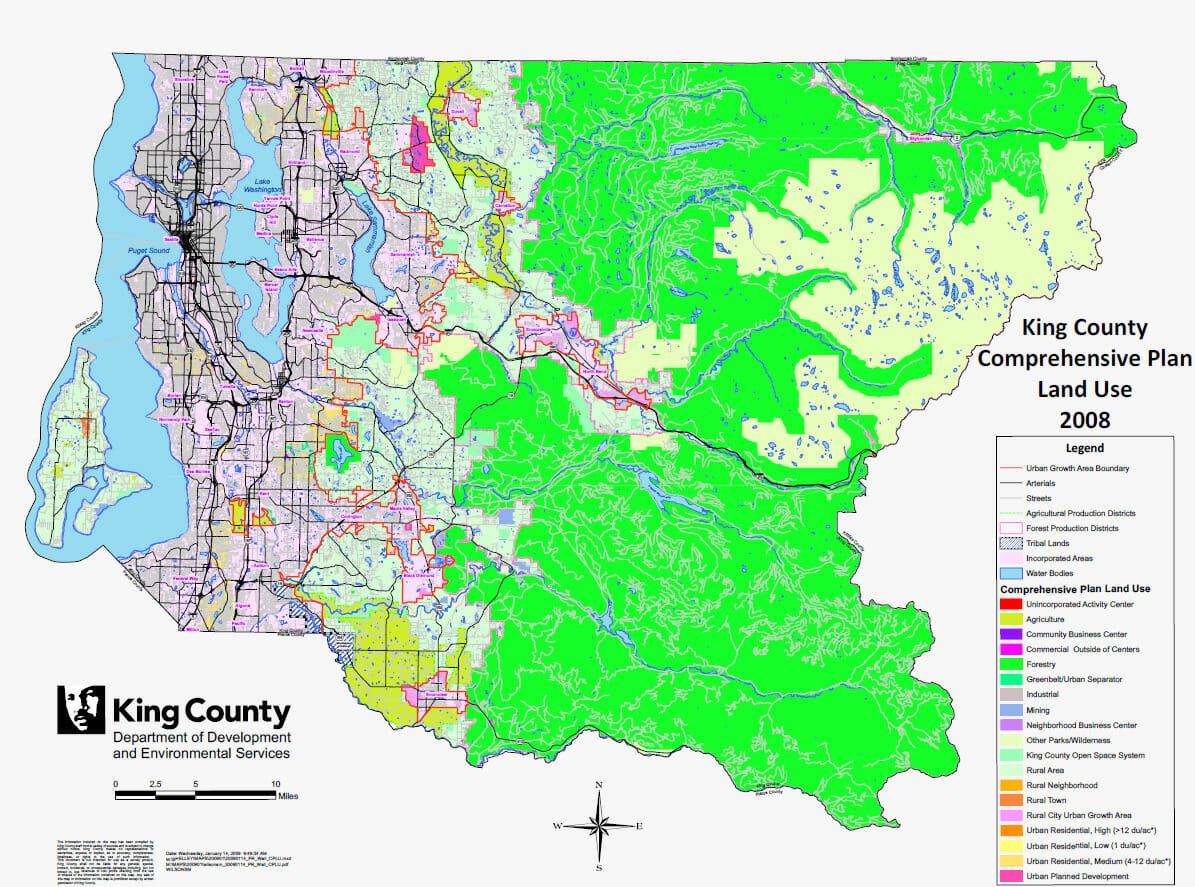

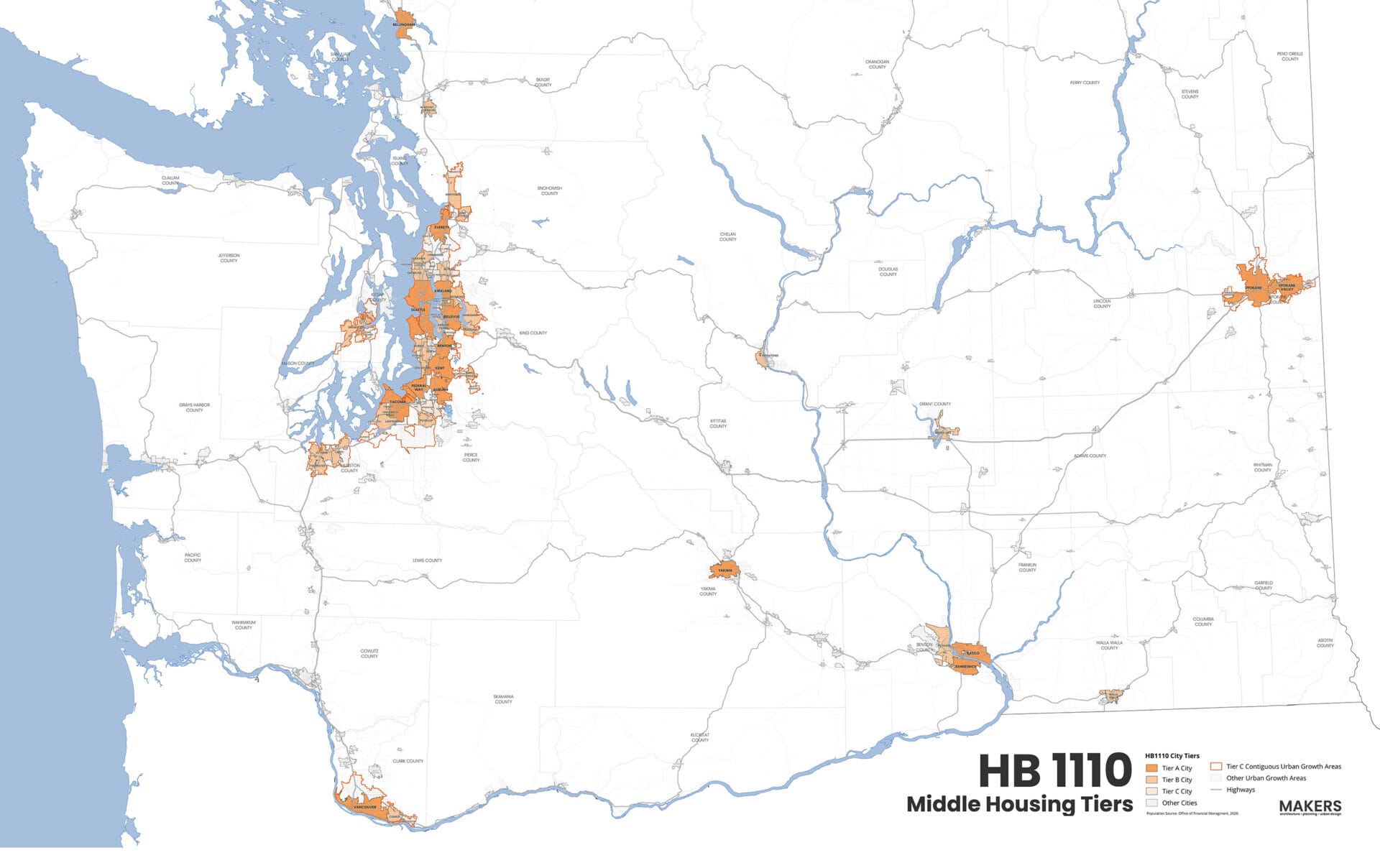

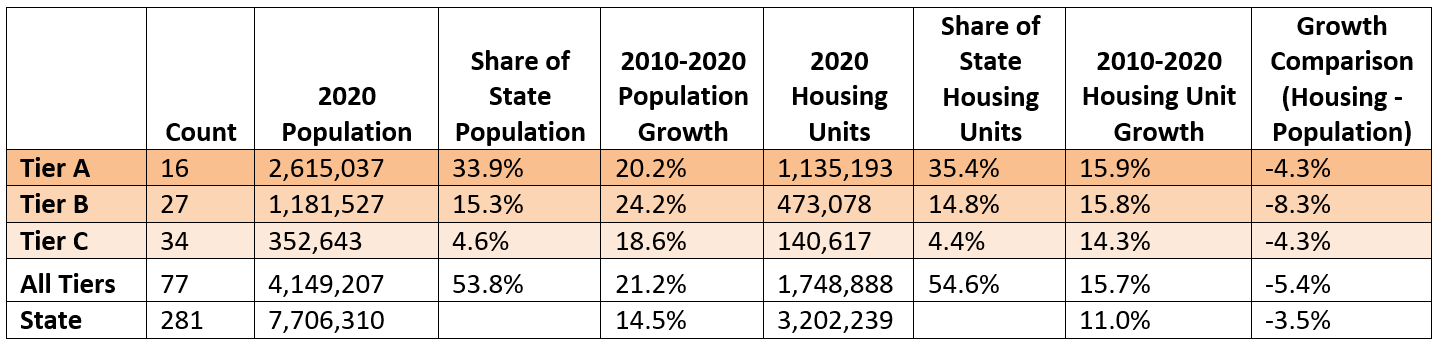

MAKERS’ analysis finds that the bill’s minimum dwelling unit allowances provisions apply to 77 of the 281 municipalities in Washington, representing a slight majority (54.8 percent) of the state’s population. Unincorporated county lands are not affected by the bill. From 2010 to 2020, the applicable municipalities grew 21 percent in population, significantly more than the statewide growth of 14 percent. However, these municipalities’ population growth has also outpaced the 15.6 percent increase in their collective housing stock.

HB 1110 sets up three levels of zoning preemptions which we label as Tier A, B, and C:

- Tier A: Cities with at least 75,000 people. These cities must permit at least four homes per residential lot, and six per lot if located within a quarter-mile walking distance of a major transit stop or if two of the homes are affordable.

- Tier B: Cities with less than 75,000 people but more than 25,000 people. These cities must permit at least two homes per lot, and four per lot if located within a quarter-mile walking distance of a major transit stop or if one of the homes is affordable.

- Tier C: Cities with populations under 25,000 and within a contiguous urban growth area with the largest city in a county with a population of more than 275,000. These cities must permit at least two homes per residential lot.

For Tier A and B, a “major transit stop” is newly defined in the GMA as any stop for bus rapid transit, light rail, commuter rail, other rail or fixed guideway systems (presumably including streetcars and Seattle’s monorail and trolley bus systems). On a related note, WSDOT’s Frequent Transit Service Study is a great start to identifying the quality of transit service available in communities across the state.

For Tier A and B, affordability covenants must be in place a minimum of 50 years and the default price restrictions are set by the GMA’s definition of “affordable housing”:

Residential housing whose monthly costs, including utilities other than telephone, do not exceed 30 percent of the monthly income of a household whose income is:

(a) For rental housing, 60 percent of the median household income adjusted for household size, for the county where the household is located…

(b) For owner-occupied housing, 80 percent of the median household income adjusted for household size, for the county where the household is located…

For Tier C, the definition of “contiguous urban growth area” is explored further in the Methodology section below. Exemptions are also discussed below.

Applicable Cities

Here is the list using 2020 population data, sorted from largest to smallest. Year 2020 is the reference point in the bill.

Note that the GMA defines “city” as “any city or town”, so municipalities classified as towns (e.g. Beaux Arts Village, Hunts Point, Yarrow Point, and Steilacoom) are applicable.

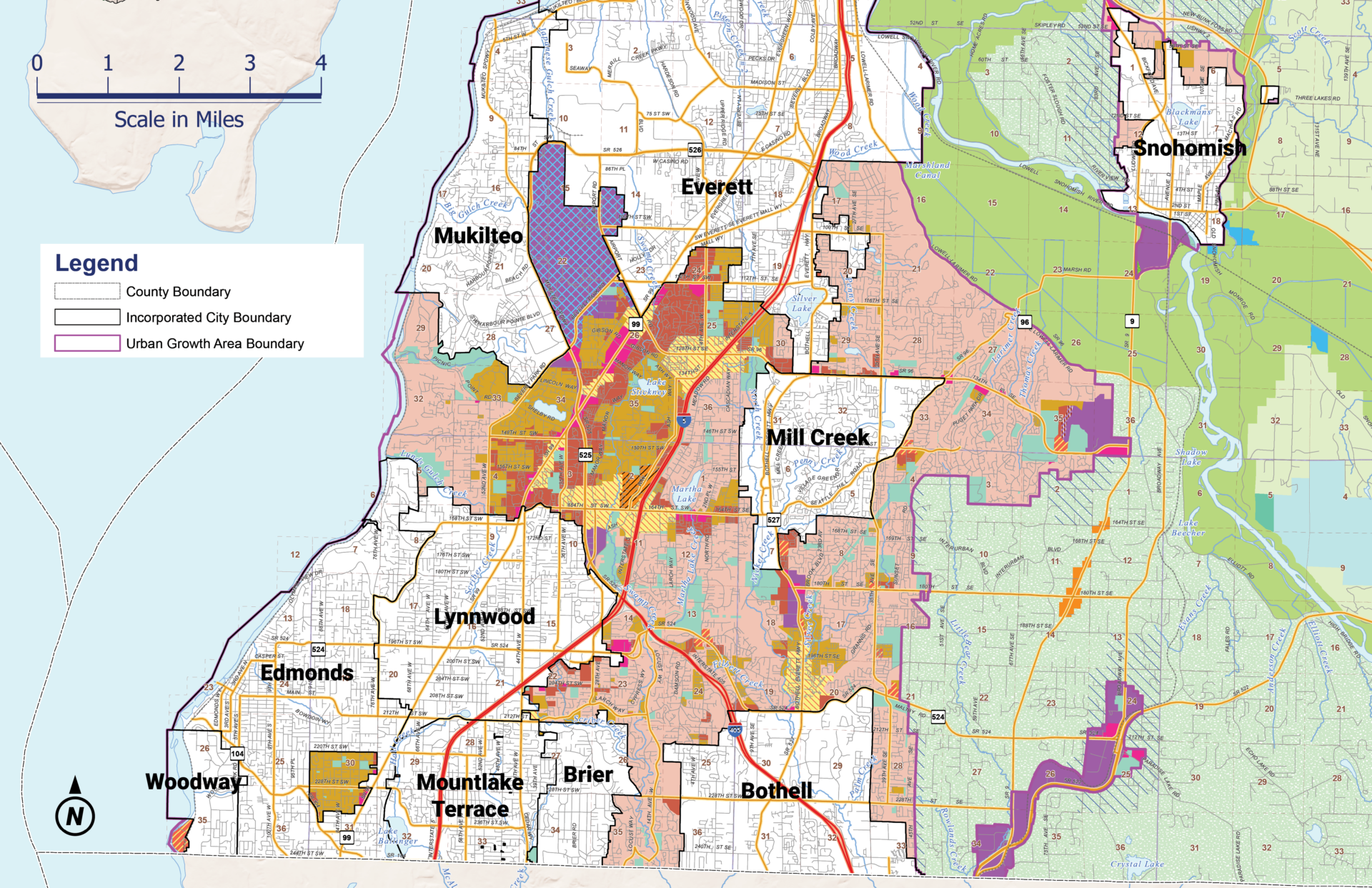

Statewide map of HB 1110 applicability to municipalities (click the image to view in high resolution)

A summary of the tiers follows. In all of the city groups, housing is being built more slowly than population is being added and the lag is larger in the HB 1110 cities than statewide.

Effect

Effect

As significant as the preemptions appear, the bill does not entirely end single-family zoning in Washington. Most municipalities are exempt. Further, the bill allows accessory dwelling units (ADU) to count toward the minimum allowances. Neighborhoods where only detached single-family and accessory homes are permitted and other housing types are prohibited are still under single-family zoning. Many Tier B and C municipalities which allow ADUs may not need to change much in their zoning codes and infrastructure plans where they already allow ADUs on residential lots, even under the related new preemptions of HB 1337 which requires all cities and counties in the state to permit at least two ADUs per residential lot.

Outside of major transit walksheds, minimum compliance in Tier B and C will result in at least three dwelling units being permitted on all lots. It’s possible that these municipalities will also need to permit duplexes, two-unit townhouse buildings, and two-unit cottage developments as principal units under a vague provision of HB 1110 that says, “A city must allow at least six of the nine types of middle housing to achieve the unit density required…” Interpretation from the Department of Commerce may be necessary.

Only in Tier A cities will single-family-only zoning be mostly retired, along with parts of Tier B cities with good transit access. However, there are more caveats, since cities seeking loopholes could also attempt to only use combinations of ADU permissions to meet the minimum requirements. In addition, HB 1110 has no effect on the many neighborhoods and subdivisions governed by homeowner associations which privately ban middle housing; some of these include the state’s wealthiest neighborhoods and the bans cannot be retroactively annulled by the state. However, going forward, HB 1110 prohibits new homeowner association rules and private contracts from prohibiting middle housing (example here in subsection C).

Updating land use tables often won’t be enough. HB 1110 also prohibits development regulations which are more restrictive for middle housing than single-family homes. For example, Millwood won’t be allowed to require a larger minimum lot size for duplexes in its UR-2 and UR-3 zones, and Washougal won’t be allowed to require that duplexes and townhouses go through a planned unit development process which has increased minimum lot size and requires hearing examiner approval.

State preemption is no reason for communities to wait in updating their zoning or going beyond the minimum requirements. Other cities outside of HB 1110’s purview already meet the spirit of the bill and promote middle housing. Port Angeles allows duplexes and cottage housing in its lowest intensity zone and Ridgefield allows duplexes, triplexes, cottages, and townhouses in its lowest intensity zone. Walla Walla updated its code in 2018 to consolidate residential zones and allow higher lot coverage, smaller setbacks, no minimum lot sizes, and reduced parking requirements. Of course, zoning is not the only factor, and many variables such as builder preferences and market conditions affect what type of housing will be built on a site with flexible zoning.

Planning jurisdictions will also need to ensure their current infrastructure and capital facilities plans are up to the task of supporting middle housing. In many cases, infrastructure will be adequate since the load from increased residents of middle housing is modest and the increase in density will be spread out over a long period of time. Most residential neighborhoods are already developed with buildings that have lifespans of 50-100 years, and individual properties’ redevelopment happens piecemeal and gradually.

Methodology

For the population-based thresholds, the bill refers to the 2020 data published by the Washington Office of Financial Management (OFM). Using 2020 data instead of the most recent 2023 data has notable effects:

- Bainbridge Island avoids any applicability (2023 population: 25,180)

- Redmond is Tier B instead of Tier A (2023 population: 77,490)

Tier A is straightforward – all cities above 75,000 in population. Similarly, Tier B is simply all cities with 25,000 or more but less than 75,000 population.

Tier C cities qualify as: “…a population of less than 25,000, that are within a contiguous urban growth area with the largest city in a county with a population of more than 275,000, based on office of financial management population estimates…”

Some planners have reported ambiguity on whether the 275,000 figure applies to cities or counties. However, the language constructs the clear phrase “county with a population of more than 275,000.” If the language was intended to apply only to Seattle (the only city above 275,000 people in the state), there is no reason to mention counties at all. Another bill written by some of the same legislators singles out Seattle by describing it as a city above 700,000 and located west of the Cascade Mountains. The 275,000 threshold is suspiciously specific and just under the 2020 population of Kitsap County (275,611), indicating this is intended to capture all of the fast-growing central Puget Sound region in addition to other large metro areas.

The Tier C counties and their largest cities, in order from largest to smallest county populations:

- King – Seattle

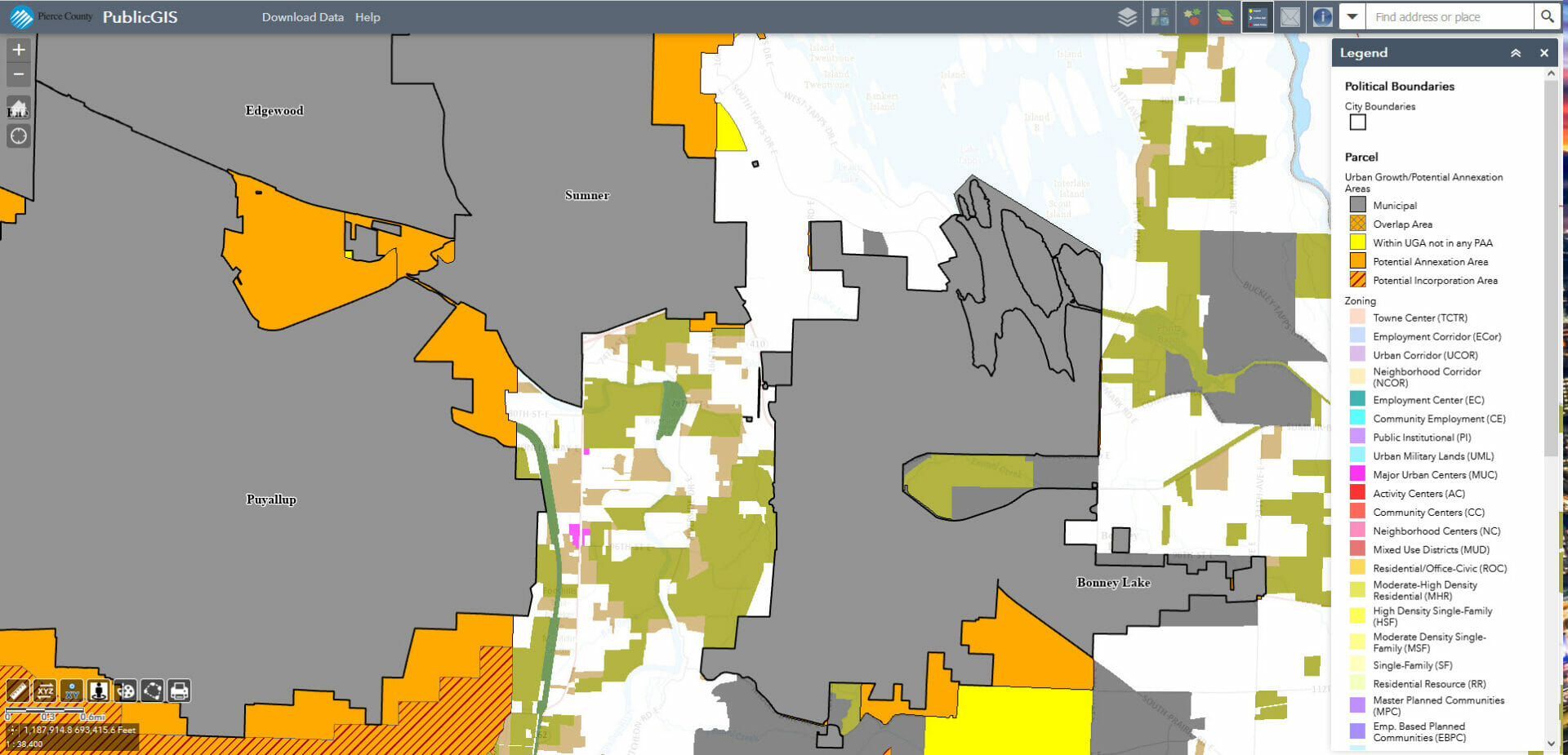

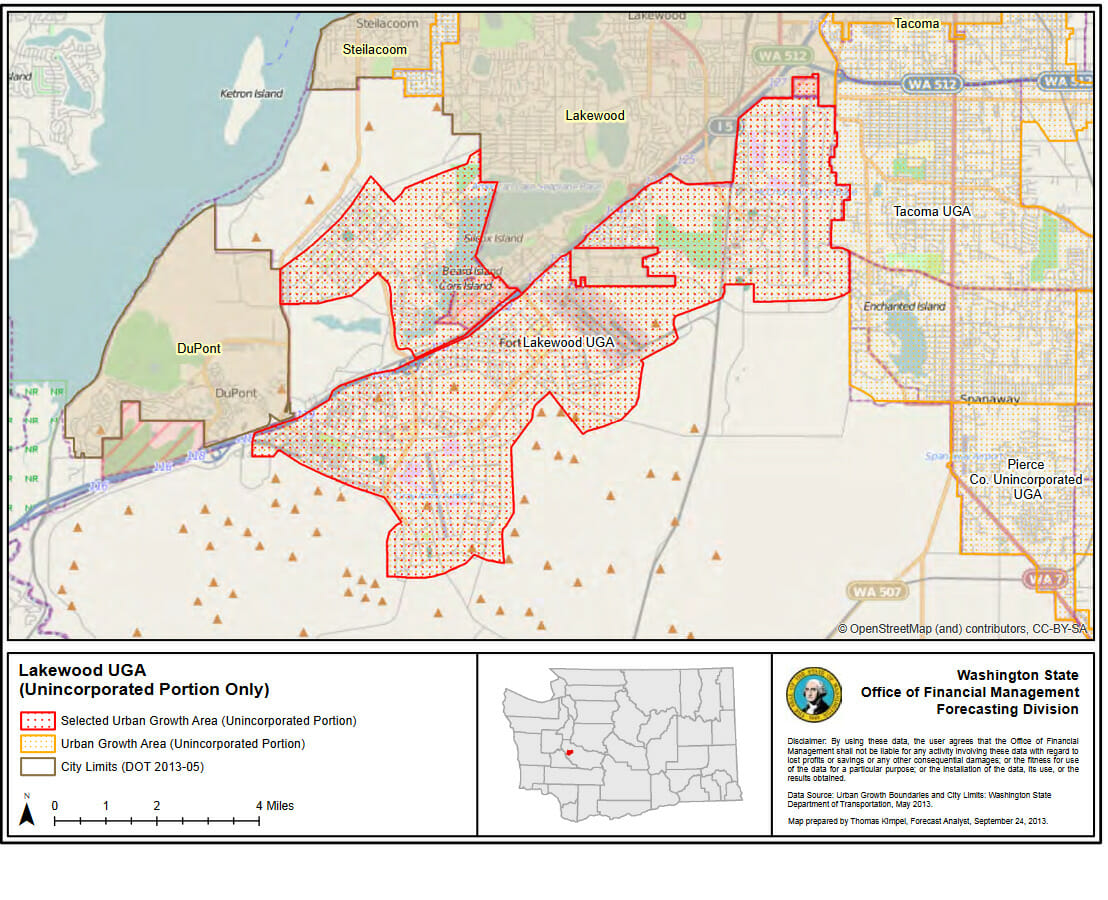

- Pierce – Tacoma

- Snohomish – Everett

- Spokane – Spokane

- Clark – Vancouver

- Thurston – Lacey

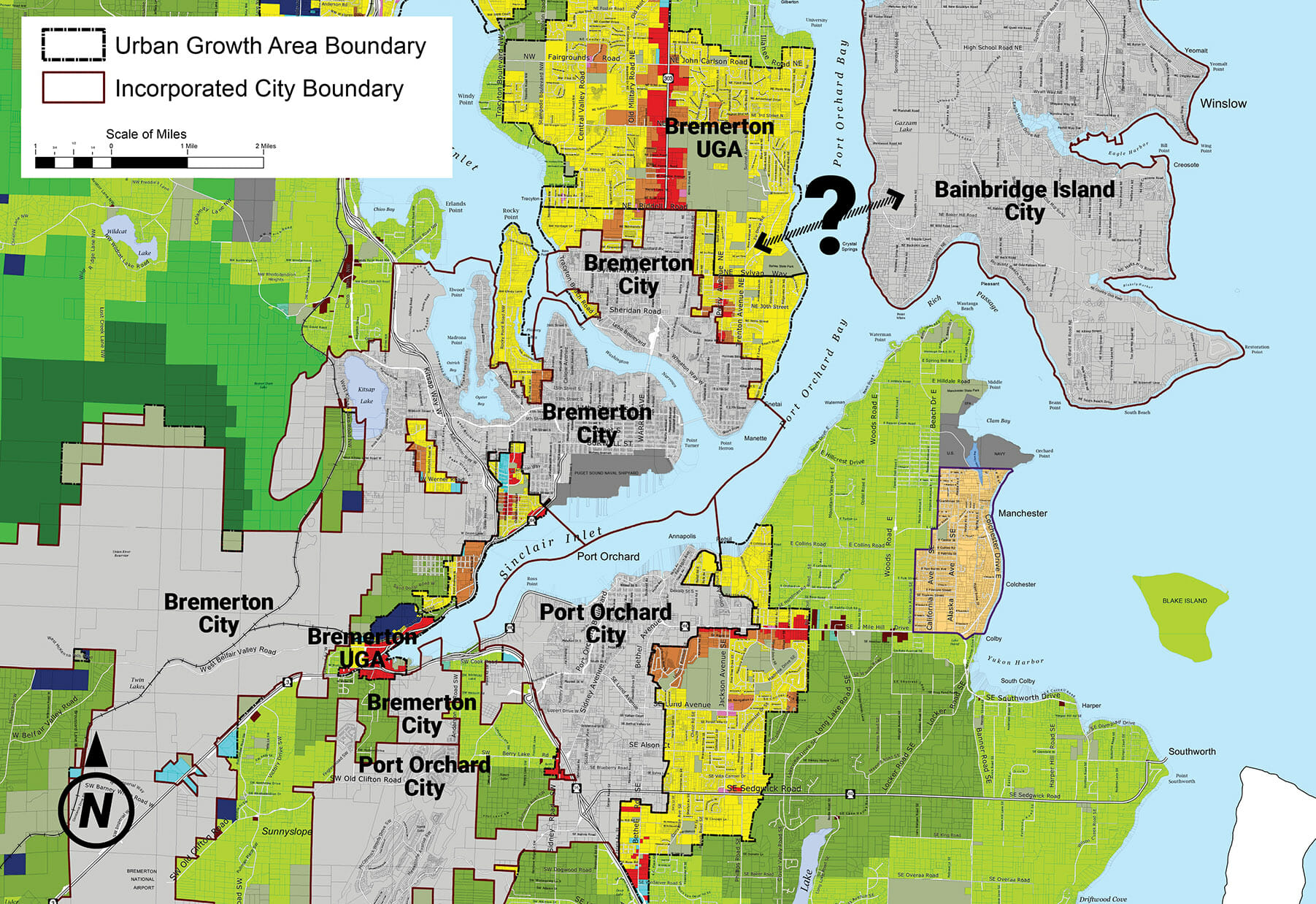

- Kitsap – Bremerton

The GMA defines “urban growth areas” (UGA) as those areas designated by a county under RCW 36.70A.110. The GMA does not define “contiguous”, so we turn to the Merriam-Webster dictionary which provides two versions that apply to geography:

- contiguous: being in actual contact : touching along a boundary or at a point

- contiguous: touching or connected throughout in an unbroken sequence

From here, we sorted and filtered through OFM data and then visually reviewed those counties’ land use maps and UGA boundaries. In most cases, it is straightforward to review of the chain of smaller cities that connect to the largest city in the county. In some locations a closer inspection was needed. Note: MAKERS makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, as to accuracy or completeness of our findings on HB 1110’s applicability to municipalities. A land use attorney should be consulted if there is any ambiguity for a municipality that needs to be resolved.

There are gaps in incorporated areas, such as in southwestern Snohomish County. However, the UGA boundary (purple line) stretches across that gap and is contiguous up to Everett, so a cluster of cities are included. The city of Snohomish, however, is in its own detached UGA and therefore excluded.

Sinclair Inlet appears to separate Port Orchard from Bremerton, the largest city in Kitsap County, but Bremerton annexed land on the south side of the inlet some years ago and the two cities actually have abutting city boundaries. This is the case even though that section of Bremerton is separated from the rest of the city (an unusual practice), since there is an area of unincorporated UGA that connects the outpost to the bulk of the city; even without that, the bill does not apply any physical size or distance limitations, so Bremerton is Bremerton.

The applicability of Bainbridge Island to Tier C is a question. The entire island is incorporated and it is across a bay from the unincorporated Bremerton UGA. It’s unclear why some municipal limits around the state are mapped into the center of navigable waterways and others are set at the low water mark. We posit that mapping inconsistencies for municipalities and UGAs may be due to the lack of a clear standard. For now, the analysis concludes that Bainbridge Island is not contiguous with Bremerton and is not a Tier C city.

Bonney Lake and therefore Orting appear not make it into Tier C because of a small gap of unincorporated non-UGA land separating Bonney Lake from Sumner, which breaks the chain from Tacoma.

DuPont in Pierce County doesn’t appear to be part of a contiguous UGA with Tacoma on the County’s online map, but other maps published by OFM and the Puget Sound Regional Council show DuPont abuts a Lakewood UGA that partly overlaps Joint Base Lewis-McChord. So that small city is in.

Tiny communities like Beaux Arts Village and Hunts Point are even further separated by water from Seattle, the largest city in King County. However, the urban growth area which encompasses Seattle wraps around the entirety of Lake Washington, so they’re in. Regardless of how Mercer Island’s situation would be interpreted, it lands in Tier B with a population of 25,748. Almost all King County municipalities are affected by HB 1110.

Interestingly, there are a few cities outside of the Tier C counties that fall into Tier A or B, and so they will be relative islands in the state where HB 1110’s minimum dwelling unit allowances apply. Those includes places like Moses Lake, Yakima, Longview, and Bellingham.

Timing

Cities must adopt zoning that complies with the bill within six months of completing their next Comprehensive Plan update. That means by June 30, 2025 for cities in the central Puget Sound region (King, Pierce, Snohomish, and Kitsap counties) and in following years through 2027 for other parts of the state.

What happens when a city tips over into a new population tier? For example, since 2020 Redmond has breached the threshold of Tier A, and Kenmore is on pace to be in Tier B by the end of the decade. The deadline for cities that later join or move up the ranks is generous. Such cities must comply with the minimum allowed dwelling unit requirements no later than one year after their next implementation progress report required under RCW 36.70A.130, and those reports are due five years after the latest comprehensive plan adoption. So, in theory, Redmond will need to comply with Tier A requirements by December 31, 2030.

Municipalities may apply for a timeline extension in specific geographic areas only if they are proposing to use the alternative compliance provisions noted below (allowing middle housing on only 75 percent of residential lots). The Washington Department of Commerce reviews the applications and determines whether extensions should be granted. Timeline extensions may be granted for only the following reasons:

- A specific area is at risk of displacement as determined by the anti-displacement analysis required for comprehensive plan housing elements, and there is a plan to address the risk

- A specific area is demonstrated to lack adequate infrastructure for water, sewer, stormwater, transportation, or fire protection and the municipality has included improvements in its capital facilities plan which will adequately increase capacity

Exemptions

Jurisdictions can seek alternative compliance by legalizing the minimum unit allowances on only 75 percent of their residential lots, subject to some limitations on how those parcels are counted. Also, there are a number of universal lot-by-lot exemptions, including:

- Lots with critical areas designated under RCW 36.70A.170 or their buffers

- Lots in impaired or threatened watersheds as defined by the federal Clean Water Act

- Lots that have been designated as “urban separators” by countywide planning policies

- Lots that are currently served only by on-site sewage systems

There is a wider exemption for the minimum dwelling unit allowances related to water that applies to certain areas (not entire municipalities). The exemption is available to areas served only by private wells, private water systems with less than 50 connections, or municipal or utility water systems which do not have an adequate water supply or available connections to serve the increased number of units. The latter may provide an out for resistant municipalities. The bill has no requirement for a technical study to prove municipal or utility water systems have inadequate supply (though the Department of Commerce may still have the authority to request one), and unlike the timeline extension options there is no requirement to plan for upgrading the water service in the exempt area.

Other Housing Updates

HB 1110 contains a number of supporting provisions for middle housing that also apply to the Tier A, B, and C communities:

- Parking cannot be required for middle housing within one-half mile walking distance of a major transit stop. Elsewhere, on lots smaller than 6,000 square feet, no more than one parking space per middle housing unit can be required. On lots larger than 6,000 square feet, no more than two parking spaces per middle housing unit can be required. Cities can seek an exemption on this with an empirical study or if they are located within “one mile” of SeaTac International Airport (how that mile is measured, from the center or edges of the airport, is unclear).

- State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). Changes to parking do not require SEPA non-project review. Amendments to development regulations to comply with HB 1110 are not subject to SEPA appeal.

- Other regulations. Middle housing cannot have design and development standards nor environmental review processes which are more restrictive than those for detached single-family homes.

- Design review. Only administrative design review may be applied to middle housing developments.

- Private zoning ban. The bill prohibits new homeowner association rules and private contracts from prohibiting the development of middle housing.

- Definitions. The bill adds several new definitions to the GMA, including for “middle housing”, “single-family zones”, and several of the specific middle housing types. Planners may wish to carefully review the definitions for “cottage housing” and “townhouses” which have prescriptive quantitative requirements and determine whether local definitions need to align.

As mentioned in the introduction, the Legislature’s work did not stop with middle housing in 2023. Here is a summary of other key bills (with statewide applicability) that planners should be aware of:

- SB 5412 – Housing developments in urban growth areas that comply with a Comprehensive Plan which has undergone an environmental analysis are exempt from SEPA review.

- SB 5258 – Cities must provide a short plat procedure for unit lot subdivisions, which is a division of a parent lot into separately owned unit lots (this is often a useful tool for middle housing and affordable homeownerhip opportunities).

- SB 5258 – Also, impact fees for residential development must be lower for smaller units based on floor area, number of bedrooms, or number of trips generated.

- SB 5491 – Cities are encouraged to allow single-stairway residential buildings up to six stories tall and with up to four units per floor (currently such buildings can only be up to three stories tall).

- HB 1042 – Cities cannot use development regulations (such as density limits or parking) to prevent additions of housing within an existing building envelope in a zone that allows multifamily uses.

- HB 1181 – Comprehensive Plans must include a Climate Change & Resiliency Element.

- HB 1771 and SB 5198 – Rules are strengthened for giving mobile home park residents an opportunity to purchase the property when it is proposed for closure or conversion, and for displaced residents to receive relocation assistance.

- SB 5258 and SB 5058 – Encourages construction of small condominium buildings by modifying the procedures for construction defect actions and warranty claims and exempts buildings with 12 or fewer units and two or less stories from condo defect provisions such as extra inspections. There is a new exemption to the real estate excise tax for first-time homebuyers of condominiums (including townhouses).

- HB 1474 – Creates a statewide down payment assistance program for first-time homebuyers with income less than the area median who were themselves, or are descendants of someone who was, excluded from homeownership in Washington by a racially restrictive real estate covenant prior to 1968.

- HB 1074 and SB 5197 – Strengthened tenant protections upon move-out or eviction.

Conclusion

Washington is in a housing crisis that took decades to dig into, and it’s going to take more decades to dig out. HB 1110 is one of the many tools we’ll need to build ourselves back to a normal housing market. I am a lifelong renter and aspiring homeowner but, until now, had been increasingly convinced I’d never be able to own a piece of land and build financial equity in my own community. With my city subject to HB 1110’s provisions by 2025, I am optimistic that a variety of middle housing products will start to be available for my family in a few short years. I’m particularly interested in the opportunity to go into a fourplex, fiveplex, or sixplex development with a cooperative group of friends or family members.

Representative Jess Bateman (District 22) was the main sponsor of HB 1110, and has been inspired to lead the state on housing through her previous roles at the Olympia City Council and Planning Commission. The city of Olympia recently went through its own lengthy and controversial middle housing zoning reform that is now close to the minimum expectation of cities across the state. Jess joined me at a panel discussion on state preemption at the 2022 APA WA state conference in Vancouver, previewing many of the housing ideas and preemptions that eventually made it into law this year.

At the bill’s passage, Jess said, “Modest middle housing options like duplexes and triplexes provide more affordable options for Washington’s working families while also slowing suburban sprawl, preventing deforestation, reducing pollution-causing traffic, and protecting our watersheds. Our state needs to build over a million new homes in the next 20 years to keep up with demand and this bill will help us get there.”

MAKERS couldn’t agree more. We look forward to helping cities and towns across Washington build a better housing future for all.

Townhouses under construction in Anacortes

MAKERS’ staff Ian Crozier, Markus Johnson, Anne D’Mura, and Bob Bengford contributed to this article.

Effect

Effect