As COVID-19 spread around the globe, communities and nations were impacted and have reacted in vastly different ways. The pandemic has spurred lively discussion and debate around urban design and how cities spread contagious diseases. The pandemic has also put a spotlight on social and economic issues that must be addressed.

The topic is particularly important to MAKERS’ ongoing work with local communities in encouraging infill housing development to accommodate critical growth needs and address housing affordability. In more than one community we are working with, planners and residents have brought up fears that residential density directly makes the pandemic worse and should be avoided. Public officials have amplified this: New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said in March, “There is a density level in NYC that is destructive … NYC must develop an immediate plan to reduce density.”

From our team’s own read of the pandemic data and medical research, along with our deep knowledge of how residential development is designed and functions, we were compelled to highlight evidence showing that that residential density and the COVID-19 pandemic have a weak relationship. Our planners are duty-bound by a code of ethics to serve the public good and rely on factual information. We will keep this post updated as more information comes in from health authorities, planning practitioners, and research institutions around the world.

Early stages

Research has found that, in the early days of a pandemic, long-haul air transportation plays a major role in spreading viruses between states and countries. This is why many of the original COVID-19 hot spots were metropolitan regions with international airports.

Once established in a community, transmission occurs effectively in non-residential settings where many people mix together, like commercial buildings, manufacturing facilities, and public venues. Common hot spots in the United States are food processing plants, prisons, hospitals, bars, and even choir practices (indoor places that are likely crowded regardless of their location). Relatedly, there is much debate about how and when schools should operate at this time.

In March, governors across the country began directing residents to stay at home and that businesses temporarily close — this discouraged people from interacting in non-residential settings and bringing the virus home. This demonstrated an understanding that limiting movement outside of residential areas would slow the pandemic. Otherwise, the orders would have been counterproductive because many people started spending more time at home than ever before.

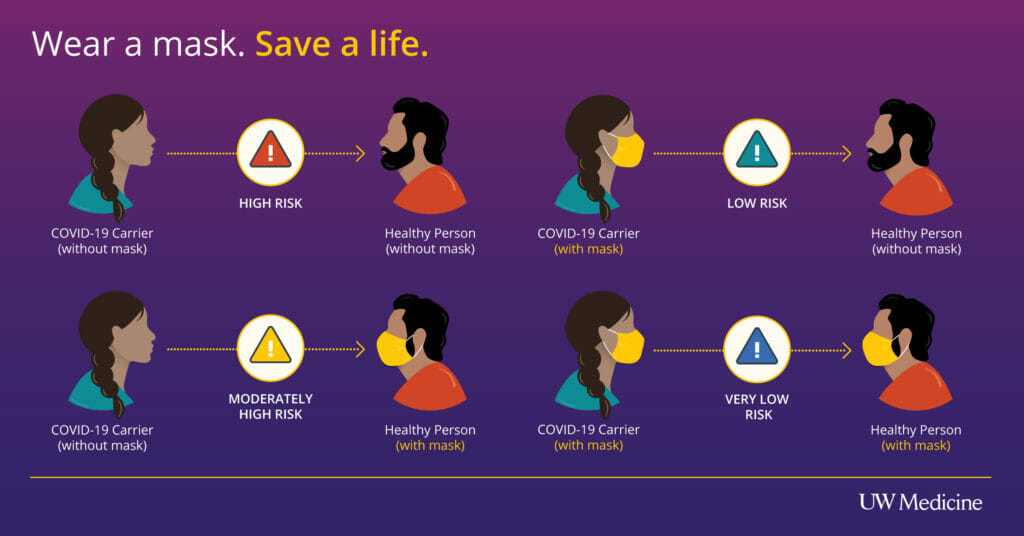

Illustration by UW Medicine

The virus spread was slowed at first, but through July we have seen a resurgence as businesses reopen and people venture out seeking normalcy. We are learning that economic stability and public health can coexist with appropriate policies. The New York Times analyzed which retail and service sectors may be least risky for transmission. The Center for Disease Control found that transmission is reduced dramatically when employees and customers wear face coverings.

Residential density versus crowding

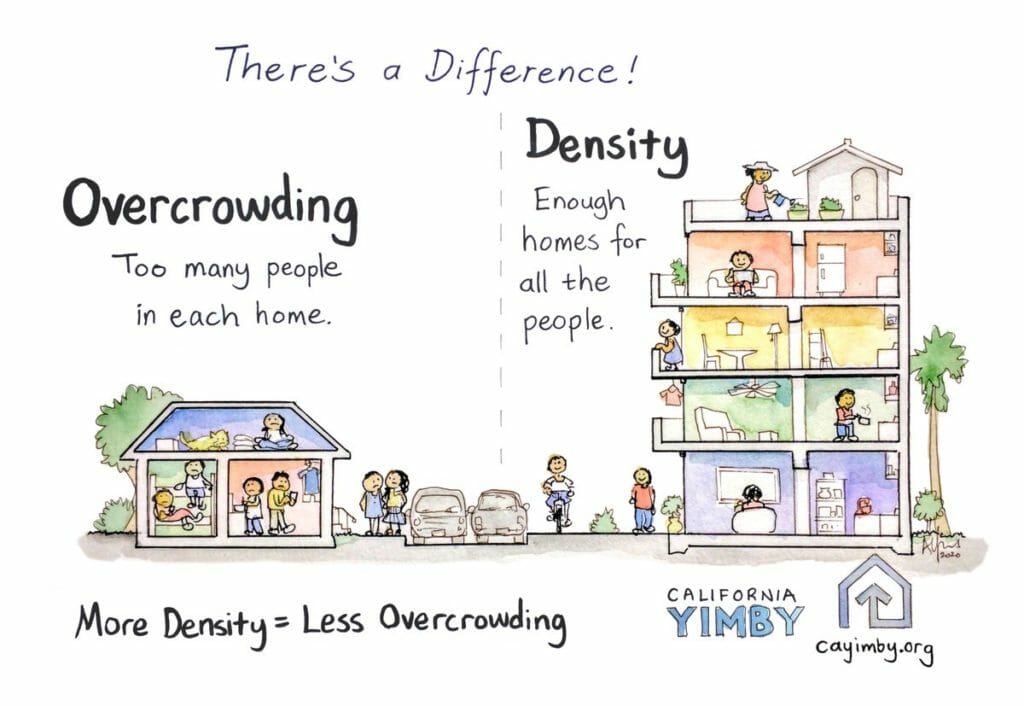

Once a virus begins community transmission, planners should know there is a difference between crowding and density. Crowding is the relationship between individuals, while density is the relationship between individuals and the physical space available to them. For example: a sold out game at CenturyLink Field is temporarily crowded, but not dense because no one lives there. A 200-unit apartment building in downtown Tacoma is permanently dense, but likely not crowded.

Illustration by California YIMBY

Crowding is normal human behavior and many of us encounter crowds in everyday life outside our homes. Destinations for daily needs like grocery stores, restaurants, schools, offices, places of worship, community centers, gyms, and other commercial and civic venues are full of people. This occurs regardless of urban, suburban, or rural context. An office or gym in Bellevue could be as crowded as another in Walla Walla. Often, this is by design, driven by consumer demand and the economics of real estate development and leasing.

Overcrowded housing appears to be a significant risk factor. For more information, see the article “Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic?” at the Journal of the American Planning Association. Researchers examined the pandemic in 913 counties and found that “connectivity matters more than density.” They recommend that “… planners continue to advocate dense development for a host of reasons, including lower death rates due to infectious diseases like COVID-19.”

Residential design

The underlying concern with residential buildings is that infection may spread between neighbors through common touchpoints and shared spaces. Higher-density developments indeed have more entryways, stairs, and elevators than lower-density developments, but elsewhere design can vary widely. Many multifamily buildings use external breezeways instead of interior corridors. In Washington, few buildings have central air conditioning. Moderate-density dwellings like detached ADUs, cottages, townhomes, and multiplexes almost always have separated private entries.

In apartment and condominium buildings, amenities like yards, decks, laundry facilities, and parking areas can be any combination of private or shared. Public health practices of wearing masks, frequent hand-washing, and covering coughs are effective at mitigating the underlying risk in these areas.

Examples of a variety of multifamily and missing middle housing types (images by MAKERS, lower-right image by Sightline)

Outdoor transmission, such as through people passing each other in parking lots and courtyards, appears to be a negligible factor. Wind, moisture, dust, and gravity play a part in dispersing any airborne virus. A Chinese study of early cases at the COVID-19 epicenter supports this idea.

A plausible concern suggested by the evidence is the virus spreads most easily through sustained, close-quartered indoor contact. Infections are frequently associated with family members living in the same dwelling. This can occur whether people are living together in an apartment or a single-family house. This may be compounded when homes have a greater number of residents or roommates due to high housing costs or an arrangement of non-nuclear, multi-generational family members, highlighting an important and long-standing equity issue.

In the same vein, in the United States major hotspots are residential nursing homes with their elderly patients and support staff. At least one-third of COVID-19 deaths, and perhaps up to half, are associated with these facilities. Elderly people have much higher hospitalization and death rates than the rest of the population. That doesn’t mean we should stop building nursing homes — in fact, we know there is a growing demand for specialized care as the senior population grows.

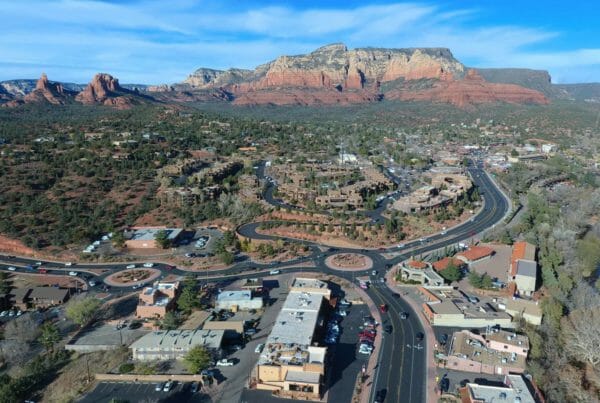

Ultimately, our daily social interactions and adherence to public health guidelines have more to do with the coronavirus spread than what type of housing we live in. As Scientific American puts it: “…Think of each city as a small forest of trees. Once lightning strikes anywhere in the city, the forest will burn until the wood runs out. Because dense cities have a larger value of contact rate of an individual … they will burn a little faster and a little longer, but what happens in New York City will be replicated in cities across the country; New York City today will be Topeka or Tucson tomorrow.”

The style and configuration of individual housing developments has little to do with how COVID-19 is spreading. Even if were, the answer would not be to “de-densify” housing stock. there is simply not enough space in our cities to build only single-family housing, and doing so would have enormous consequences for our health, society, and environment.

Housing equity

Low-income households and people of color are more likely to be renters and residents of higher-density housing in metropolitan areas. These groups are often forced into more crowded housing situations to afford costs. A Chicago study found lower-income neighborhoods with large households, despite lower land use intensity, had higher infection rates than higher-income neighborhoods.

These same groups have been disproportionately affected by job losses, infection, and death amid the pandemic. Some of the disparity may be explained by these groups more often working in “essential” jobs such as grocery clerks, warehousing, custodians, social services, and public transit — and also having less access to adequate healthcare.

If the pandemic influences communities to reduce permitted residential density, these groups stand to lose the most. Ultimately, post-pandemic housing strategies should focus on a just rebound and continue to focus on providing fair, diverse, and affordable options for all portions of the community.

Population geography

From a broader geographic view, the relationship between municipal population density and infection rates is tenuous at best. At the time of this writing, rural Yakima County has the highest rate of cases on the West Coast despite being only the eighth most populous county in Washington state and one-sixteenth the population density of King County. This is partly explained by the Yakima area’s agriculture industry; two-thirds of the county’s workers are considered essential, and a high share are Latinx. Agricultural workers travel seasonally and often live in bunkhouses with many people sharing living spaces in close proximity.

Nationwide, counties with the highest cases per capita are not metro centers but rural and suburban areas like Trousdale County, Tennessee; Buena Vista County, Iowa; and Lee County, Arkansas. McKinley County, New Mexico, part of the Navajo Nation, has also been within the top five counties. The map below shows high case rates in vast swaths of the rural Midwest and Sunbelt. Generally speaking, this is the opposite of what one may expect from looking only at population density.

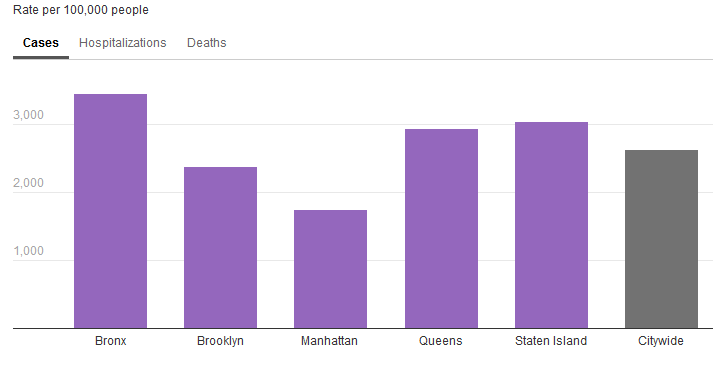

Even the situation in New York City is counterintuitive. It is the densest large city in the United States at 27,000 people per square mile. The most dense borough of Manhattan has about half the case rate of the least dense borough of Staten Island. Early studies have also suggested a minimal connection between infections and public transit.

New York City COVID-19 data courtesy of nyc.gov (July 29, 2020)

San Francisco, the nation’s second most dense city at 18,000 people per square mile, has been noted for remarkably low infection rates citywide. Credit is given to a speedier introduction of social distancing measures in March and the city’s high share of remote-capable technology jobs. It may also be because the people most susceptible to infection and working essential jobs — oftentimes low-income people and people of color — are not living in the city proper due to extreme housing costs and inequitable housing policy.

Globally, other famously high-density cities like Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Singapore have had low infection and death rates thanks to robust public health responses. Notably, Japan has had less than 1,000 deaths, compared to the United States’ 160,000 and counting, despite being 10 times more densely populated. They also have a higher share of senior citizens than any other nation. Nearly 100% mask-wearing compliance and other cultural factors helped Japan avoid lockdown measures.

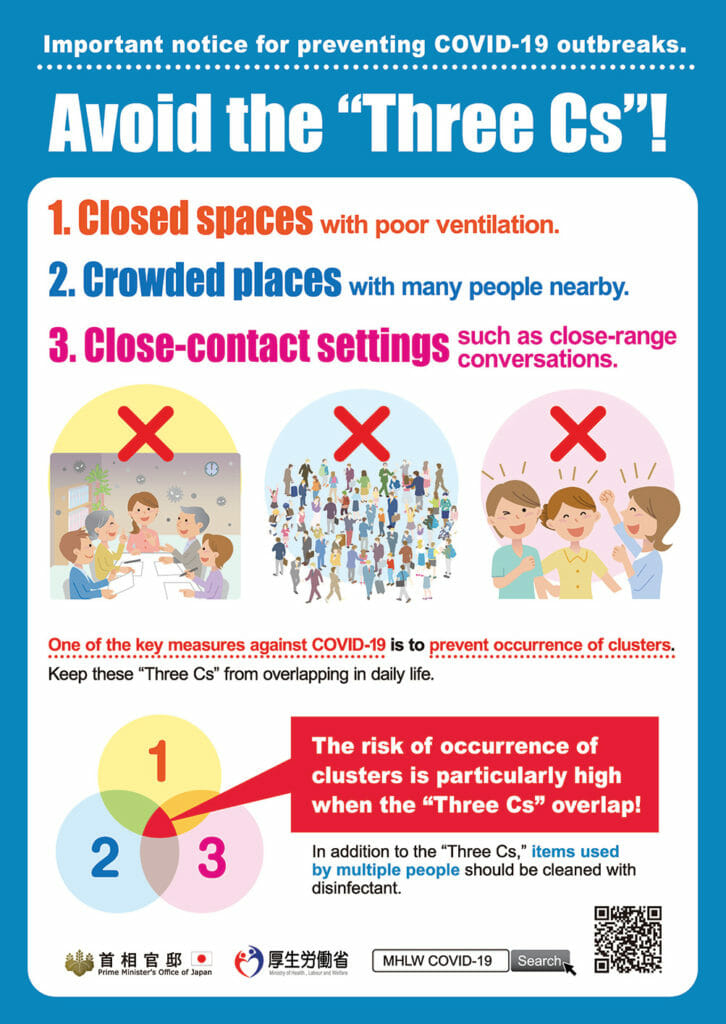

Public health poster from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare

Parks, plazas, and streets

Density concerns may also manifest beyond residential and commercial domains. As people are stuck with “stay at home” orders, working from home, or losing their jobs entirely, they continue to have needs for exercise, fresh air, and socializing. Anecdotally, more people are enjoying outdoor walks and local parks across the country.

If these outdoor spaces are perceived as crowded, it is likely not because there are too many people, but because there has long been a shortage of these spaces in urban areas. Bigger parks may be difficult to access without a car. Cities have always had the obligation to provide adequately sized and well-maintained open space in sync with the growth and needs of their residents. That responsibility is now more urgent.

Over the past century, most city streets have delegated pedestrians to the margins in favor of space and speed for vehicle traffic. Outside of most central business districts, sidewalks are often cramped for normal foot traffic, let alone the current social distancing guidelines. Too many sidewalks are also cracked by tree roots, blocked by utility poles, or lack curb ramps. These factors make walking unpleasant, not to mention hazardous and difficult for people with wheelchairs, strollers, and package carts. Areas that lack sidewalks or pathways entirely are an even greater concern.

As a result, cities are experimenting with expanding the area where it is safe and legal for people to walk, run, roll, and ride their bikes. Washington communities like Seattle, Bothell, Edmonds, and Leavenworth have made a start by closing some streets to through-traffic, but more can be done. In the post-pandemic recovery, cities are also experimenting with allowing dine-in restaurants to expand seating to the outdoors so people can be adequately separated.

Public streets closed to cars for outdoor dining in Leavenworth and Seattle, WA (photos by the author).

Density benefits

Urban planning professionals will be familiar with the many benefits of high-density living. A few lesser known factors are also worth considering. Urban areas tend to have the tax revenue that supports robust healthcare infrastructure and medical research when infections do occur. A recent study found that 80% of U.S. counties do not have a single infectious disease expert.

Citing the real concern of limited hospital capacity, rural communities across the country have asked visitors and tourists to stay away, which will impact the speed of their economic recovery.

Urban residents also tend to be healthier, on average, than their suburban and rural counterparts and therefore may be less susceptible to viruses. This is due to a variety of factors such as better healthcare access and higher rates of walking and bicycling. The article linked above included these statistics: “Just 22 percent of adult New Yorkers are obese, according to the city’s health department, compared to the 42 percent rate for the U.S. as a whole, as reported by the CDC.”

Urban-level density has long-term benefits outside of a pandemic that planners should continue to celebrate:

- Supports more public and commercial amenities.

- Supports compact communities that shrink the distance to daily needs.

- Reduces environmental impacts by encouraging smaller homes and less automobile use.

- Supports frequent and convenient transit service.

- Supports more diverse cultures and artistic opportunities.

- Supports more economic activity and business-to-business relationships.

Planners should know rule-of-thumb minimum density thresholds for supporting various urban amenities (local context, funding, and regulations will alter these for every community):

- Centralized water/sewer service: 4 units per gross acre.

- Viable grocery-based neighborhood business district: 10 units per gross acre.

- Frequent bus service in walking distance: 10-15 units per gross acre.

- Light rail or bus rapid transit service: 15-25 units per gross acre.

The takeaways

Density is a quantitative unit of measurement. Planners have long known that concerns citing “qualitative density” can be red herrings or proxies for other concerns: displacement, gentrification, traffic, parking, views, trees, architectural aesthetics, renters, crime, etc. The lack of numbers offered by skeptics can be telling: Is 10 people per acre acceptable? What about 20? 50? 100? And are we measuring gross acres or net acres?

Planners should be on the lookout for this tactic and have the facts on hand for decision-makers well after the pandemic subsides. Planners should also engage sincerely with the communities they work in to hear out concerns and find equitable and fair solutions.

Planners can show evidence that the benefits and impacts of residential development depend on factors beyond the number of people living on a property. The visual impressions from building design, the site’s relationship to the street, the ground floor use, landscaping design, trees, and parking configuration are what is most obvious to the community. Planners might find that educating their constituents on design issues, and focusing their work on good urban design, can adequately address concerns.

For more discussion resources on a variety of post-pandemic urban planning topics, see MAKERS’ other blog post, COVID-19 urban planning discussion resources. See also: Partner Bob Bengford’s MRSC article on visualizing compatible density.